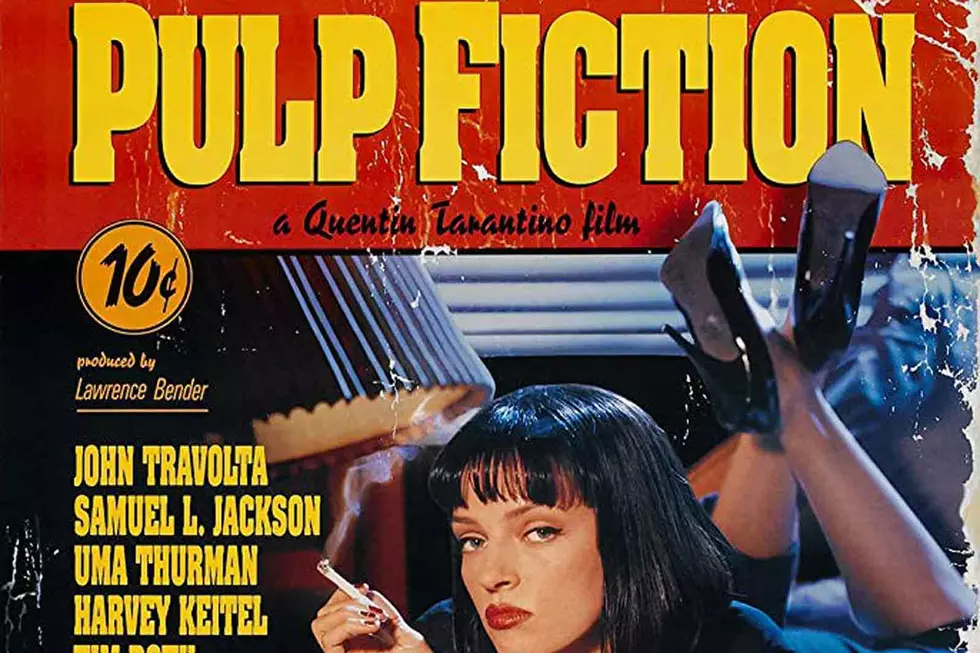

25 Years Ago: ‘Pulp Fiction’ Launches a Movie Revolution

Quentin Tarantino once remarked during an interview that the widespread shift to making movies with digital cameras was "the death of cinema as I know it."

This is a common refrain for Tarantino, an outspoken advocate of shooting and showing movies on film. One of his primary worries seems to be that the ascendance of digital technology will mean there's no longer any reason to go to a theater, because everyone can watch high-quality digital on their TVs.

This belief in movies as a public form – meant to be shown at theaters and experienced communally – explains a great deal about Tarantino's art. And it offers a particular insight into his second and greatest film, Pulp Fiction, which came out on Oct. 14, 1994.

There are many ways to understand the legacy of the movie. It resurrected the career of John Travolta and jump-started the careers of Samuel Jackson and Uma Thurman. It was one of the crown jewels of the independent-cinema movement of the '90s and brought to the mainstream an artistic sensibility combining irony, intelligence and earnestness that had been lurking mostly underground for years. It is often, and rightly, regarded as one of the greatest American films of the 20th century.

But as Tarantino's career has moved forward through its subsequent highs and lows, what perhaps stands out the most about Pulp Fiction is its commitment to movies themselves, as entertainment, as spectacle and as a shared obsession. This commitment begins with the movie's famously complicated structure, which mixes timelines and stories in a way that's continually surprising but never threatens to lose the viewer.

One storyline is about a pair of gangsters, Vincent (played by Travolta) and Jules (Jackson) on a mission to recover an unnamed object in a suitcase for their boss. After retrieving this McGuffin, they accidentally kill one of their compatriots in the backseat of their car and need to get it cleaned in a hurry. Another storyline involves a boxer (Bruce Willis) who throws a fight and then realizes he has to go back to his old apartment to pick up a watch his father gave him before he can skip town. A third revolves around Vincent's night chaperoning his boss' girlfriend Mia (Thurman), during which she overdoses and has to be resurrected with a shot of adrenaline to the heart.

What no summary can do justice to is the elegance of the way these stories – each of which has several other smaller sidelines – are interwoven. It's a structure that gives the whole an almost magical feel, admixing the high-art approach of something like Fellini's 8½ or Kurosawa's Rashomon with the gritty, grainy low-budget sensibilities of the American and Italian pulp films from the '70s that Tarantino is so fond of. It also serves as a testament to Tarantino's faith in the cinematic intelligence of his audience. It's clear that he believes they can follow him through every twist and turn of his vision and that it's not necessary to pander in order to entertain.

Laid over this structure, Tarantino's script (based on scenarios invented by both Tarantino and Roger Avery) provides an almost never-ending stream of extraordinary dialogue.

Tarantino has always taken great pride in his abilities as a writer – he often calls them "my dialogues" – and regardless of how well or poorly this skill has aged, it's on display at its absolute finest here. There are funny lines and quotable lines and verbally dexterous lines; there are meditations on coffee and the nature of hold-ups and Vietnam and the Bible and the art of the foot massage. And this dialogue never feels untrue to character, never feels as though it is coming from the pen of the writer or exists for his vanity. Instead, it simply feels as though we've stumbled into a world where the coolest people possible say the coolest things imaginable. It's in no small part this writing that lets the acting shine as much as it does. Give a talented cast a script like this, and they will eat it up.

Watch 'Pulp Fiction' Trailer

Visually, Tarantino is at his best here as well. He is not, despite his reputation, a flashy visual director. Rather, he combines a remarkable flair for color and composition with an almost classicist devotion to making every shot the right shot. He does not move his camera capriciously but always with intention. He uses inserts judiciously and precisely. And he chooses compositions that highlight story, character and acting rather than his own ego.

The result is a movie that operates on many registers, from the cartoonish to the macabre, and is full of references to film, television and the Technicolor feel of pop culture itself. Plus, the contributions of cinematographer Andrzej Sekuła (who also shot Tarantino's first film, Reservoir Dogs, in 1992) and editor Sally Menke (who cut Tarantino's first seven movies, through 2009's Inglorious Basterds) are paramount in the creation of this.

But what does all of this have to do with Tarantino's belief in the importance of movies as a public medium? The digital movie experience is, in many ways, disposable. The introduction of streaming platforms, the ease with which movies are now pumped out and forgotten, the act of sitting on a couch alone in a living room and watching a movie while thumbing through apps on your phone – all of this seems to run counter to what Tarantino loves about cinema.

He loves the grandness of it, the feeling of being overawed by larger-than-life characters on a 90-foot screen. He loves the history of it, the famous actors and the minor ones, the directors everyone knows and the directors everyone has forgotten. He's an archivist who has a huge collection of films on celluloid, and he owns a theater in Los Angeles where he programs double-features of old films every night.

It is this love of the history and spectacle and mythology of cinema that bleeds out from every frame of Pulp Fiction. It's a movie meant to be seen with popcorn in one hand and a soda in the other, in a packed theater; it's meant to be talked and debated about, and meant to serve as a touchstone that other filmmakers can reference and rip off and use in their own attempts to make something beautiful. Just like Tarantino himself did with the movies he loved.

The Best Rock Movie From Every Year: 1955-2018

More From 98.3 The Snake